CGD Policy Paper 221

July 2021

Binding Constraints on

Digital Financial Inclusion in

Indonesia: An Analysis Using

the Decision Tree Approach

www.cgdev.org

Center for Global

Development

2055 L Street NW

Fifth Floor

Washington DC 20036

202-416-4000

www.cgdev.org

This work is made available

under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial 4.0 license.

Despite the concerted eorts of the Indonesian government to increase financial inclusion

and the e-commerce–led growth of digital payment services, a large proportion of the

country’s population remains financially excluded. Much of the growth and innovation has

mainly benefited those already financially included.

To understand this outcome, we use the decision tree approach developed by Claessens and

Rojas-Suárez (2020), focusing on one of the products with the largest potential to increase

financial inclusion in the country: e-money.

Our analysis finds that a crucial binding constraint on the expansion of e-money services

is a regulatory framework that creates an unlevel playing field between banks and nonbank

providers of digital financial services. Regulatory restrictions applied to nonbanks on cash-

out services, agent recruitment, and know-your-customer processes are at the core of the

problem. In addition, a perception of low benefits from the usage of formal financial

services results in a lack of the critical mass of customers necessary to ensure the profitability

of agents, particularly in remote and rural areas, and thus the expansion of e-money services.

We also find other constraints that are not binding at the national level but are binding for

some specific groups. The low provision of digital infrastructure in rural areas outside Java

is one of them. In addition, constraints such as low trust in providers, though not binding,

should be addressed in order to maximize the gains that could be obtained from relaxing the

binding constraints.

Abstract

Firman Witoelar, Teguh Yudo Wicaksono,

and Carlos Mangunsong

Center for Global Development

2055 L Street NW

Washington, DC 20036

202.416.4000

(f) 202.416.4050

www.cgdev.org

The Center for Global Development works to reduce global poverty

and improve lives through innovative economic research that drives

better policy and practice by the world’s top decision makers. Use and

dissemination of this Policy Paper is encouraged; however, reproduced

copies may not be used for commercial purposes. Further usage is

permitted under the terms of the Creative Commons License.

The views expressed in CGD Policy Papers are those of the authors and

should not be attributed to the board of directors, funders of the Center

for Global Development, or the authors’ respective organizations.

Binding Constraints on Digital Financial Inclusion in Indonesia:

An Analysis Using the Decision Tree Approach

Firman Witoelar

Australian National University

Teguh Yudo Wicaksono

Mandiri Institute

Carlos Mangunsong

DTS Indonesia

The authors would like to thank Liliana Rojas-Suarez and Alejandro Fiorito

Baratas from the Center for Global Development for their guidance and

feedback in the development of the project. The paper has benefited from

the discussions with Djauhari Sitorus and Rifki Akbari (National Council

for Financial Inclusion of Indonesia/DNKI), Ida Rumondang Sipahutar

(Indonesian Financial Services Authority/OJK), I Gede Putra Arsana

(The World Bank), Dwinita Larasati (Coordinating Ministry for Economic

Aairs), and Praswistiadi Syamsuri (Indonesia Fintech Association/

AFTECH), and from feedback from two anonymous reviewers. Finally,

we would like to thank Natanael Waraney Massie for providing invaluable

research assistance throughout the project. All errors are our own.

The Center for Global Development is grateful for contributions from

the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in support of this work.

Firman Witoelar, Teguh Yudo Wicaksono, and Carlos Mangunsong. 2021.

“Binding Constraints on Digital Financial Inclusion in Indonesia: An Analysis

Using the Decision Tree Approach.” CGD Policy Paper 221. Washington,

DC: Center for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/

binding-constraints-digital-financial-inclusion-indonesia-analysis-using-decision-tree

Contents

Abbreviations .........................................................................................................................................1

Foreword ................................................................................................................................................2

1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 4

2. The digital financial system landscape: providers and products ...............................................7

3. Methodology: identifying binding constraints using the decision tree approach ..................12

4. Prices for digital payment and store-of-value services ..............................................................15

5. Supply-side constraints on payment and store-of-value services.............................................22

5.1. Market structure of banks and nonbank digital service providers ..................................22

5.2. Insucient or poor private digital infrastructure ...............................................................34

5.3. Low appropriability of returns ............................................................................................. 39

6. Demand-side constraints on payment and store-of-value services .........................................47

6.1. Perceived low or no benefits of usage .................................................................................47

6.2. Low trust in providers ............................................................................................................50

6.3. Low income and geography ...................................................................................................55

7. Conclusions ......................................................................................................................................57

8. Appendixes ......................................................................................................................................59

Appendix 1. Electronic money licenses ......................................................................................59

Appendix 2. Sources for provider-level data ..............................................................................60

Appendix 3. Key stakeholders and regulations ..........................................................................66

Appendix 4. The decision tree methodology: further details ................................................... 69

Appendix 5. Sources for account registration requirements ....................................................71

Appendix 6. Sources for telco provider–level prices ................................................................ 72

Appendix 7. Sources for institution-level fraud data .................................................................72

9. References ........................................................................................................................................74

List of figures

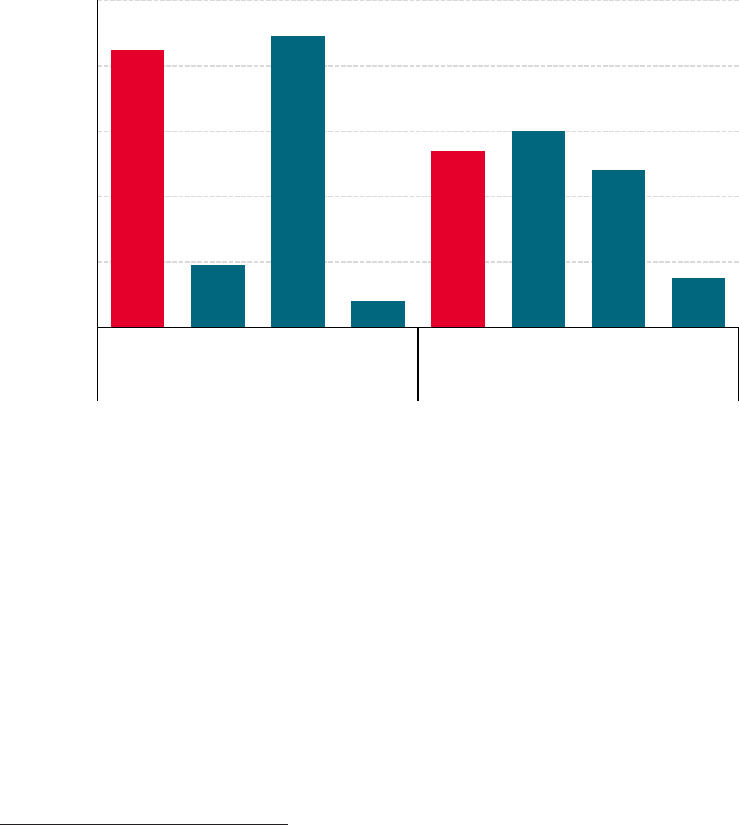

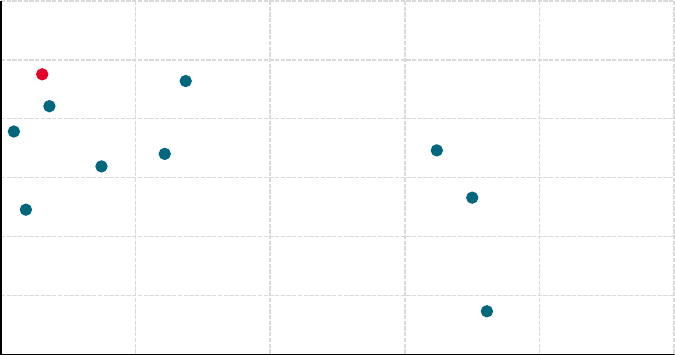

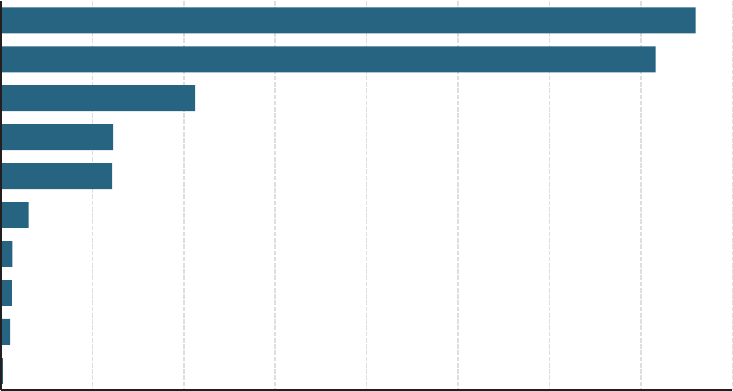

Figure 1. Formal financial products ever used, Indonesia, 2018

(self-reported use, percentage of adults 15+) ...................................................................................5

Figure 2. Use of regular savings accounts, BSAs, and e-money, Indonesia, 2014–2018 ............6

Figure 3. E-money transaction volume and nominal value as percentage

of ATM and debit card transactions, Indonesia, 2015–2020 .........................................................9

Figure 4. Method of making account withdrawals and deposits, Indonesia, 2018 ...................10

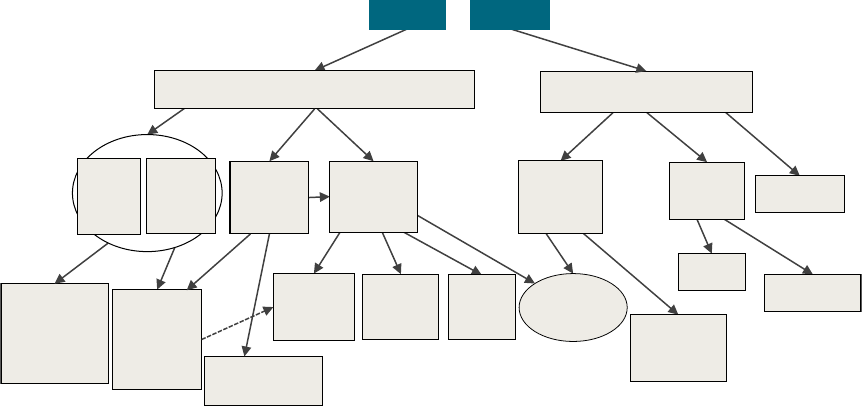

Figure 5. Decision tree for payment and store-of-value digital financial services .....................13

Figure 6. Average bank ATM withdrawal fee as percentage of daily GNI per capita,

2020, Indonesia and selected comparator countries ......................................................................16

Figure 7. ATMs per population and usage of digital payments, Indonesia and selected

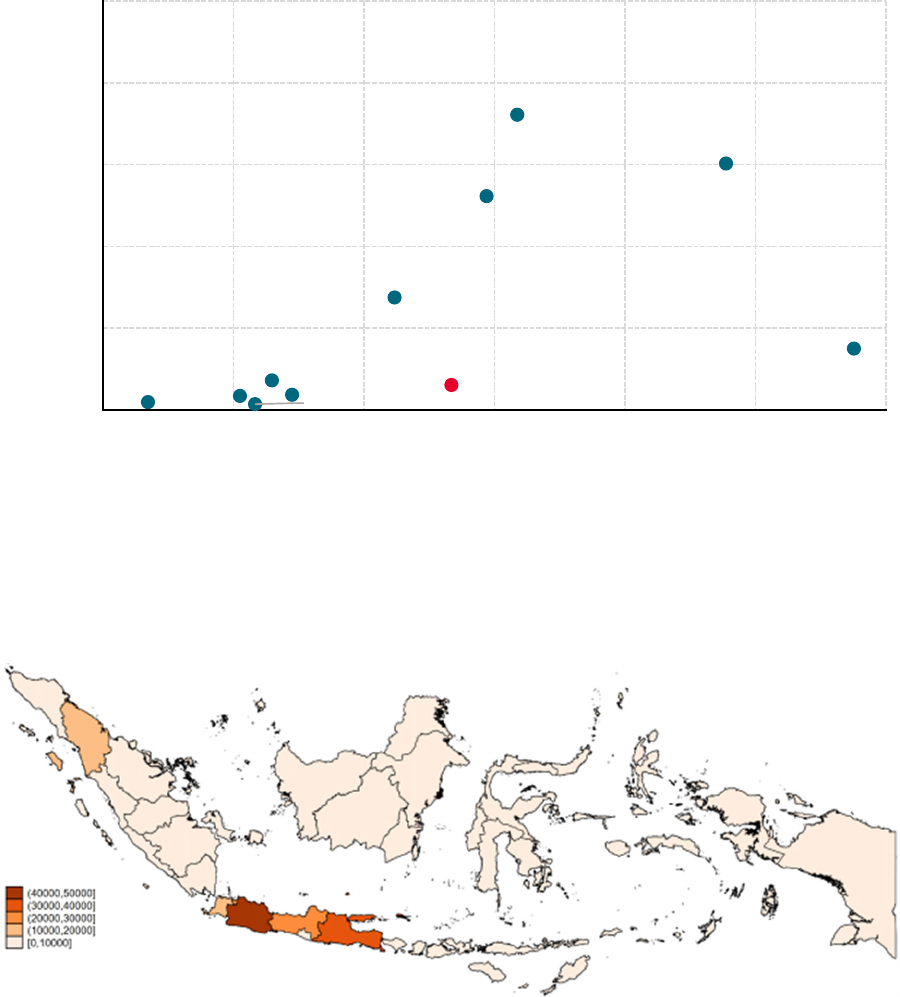

comparator countries, 2020 ...............................................................................................................17

Figure 8. Number of points of service for BSAs, including banks, ATMs,

and branchless banking BSA agents, Indonesia, 2018 ...................................................................17

Figure 9. External transfer fees for e-wallets of selected banks and e-money providers

as percentage of daily GNI per capita, Indonesia, 2020 ...............................................................18

Figure 10. External transfer fees for e-wallet transfers, as percentage of daily

GNI per capita, Indonesia and selected comparator countries, 2020 .........................................19

Figure 11. External withdrawal fee from e-wallet, as percentage of daily GNI per capita,

Indonesia and selected comparator countries, 2020 ......................................................................20

Figure 12. Average fees to open a regular savings account, as percentage of GNI

per capita, Indonesia and selected comparator countries, 2020 ...................................................21

Figure 13. Average annual administrative fee to keep a bank account, as percentage

of daily GNI per capita, Indonesia and selected comparator countries, 2020 ...........................21

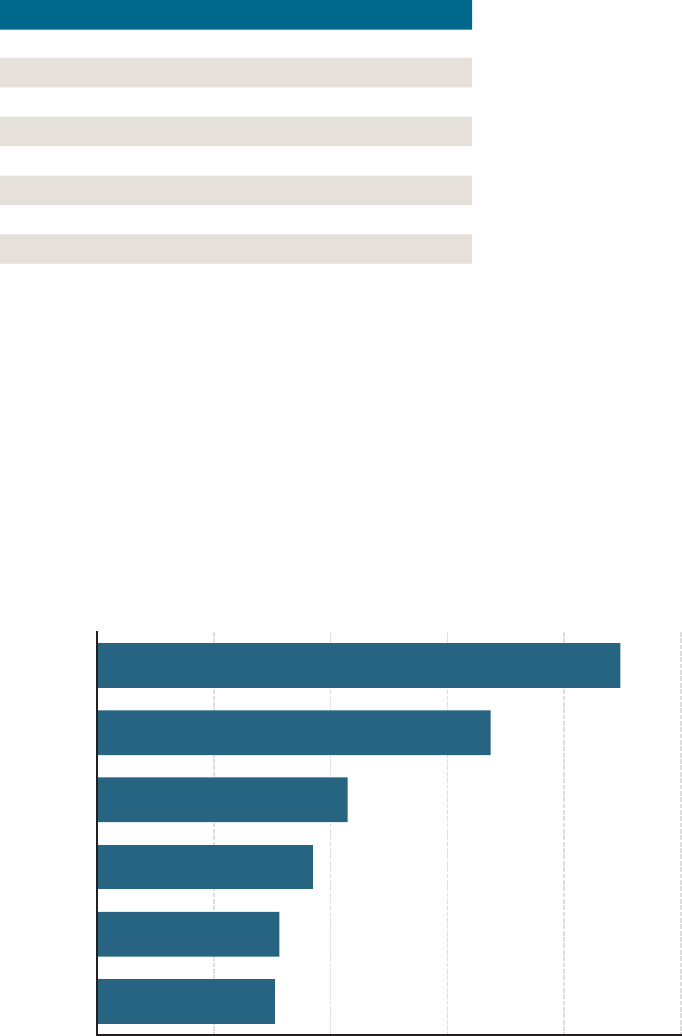

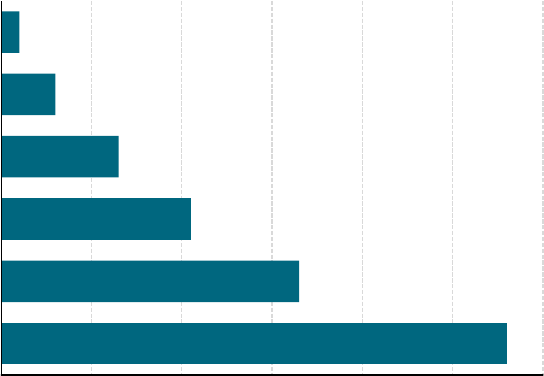

Figure 14. Top 10 commercial and retail banks by total assets, Indonesia, 2020,

IDR trillions (percentage of total assets in parentheses) ..............................................................30

Figure 15. Five-bank asset concentration (percentage of all bank assets),

Indonesia, 1996–2016 ........................................................................................................................30

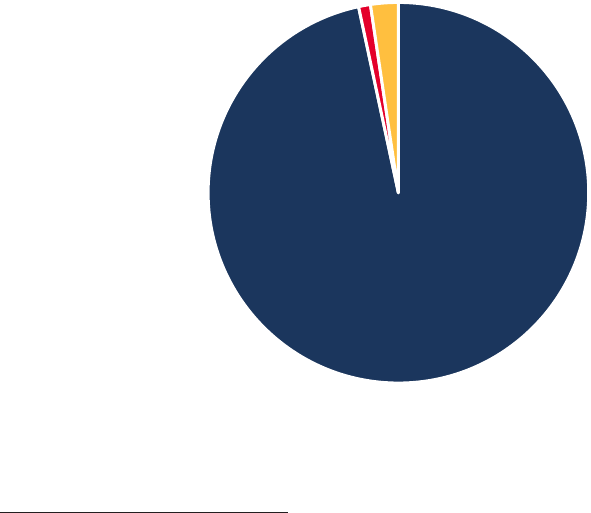

Figure 16. E-money transaction market shares, Indonesia, 2019 ................................................. 32

Figure 17. Transfer between e-money providers ............................................................................34

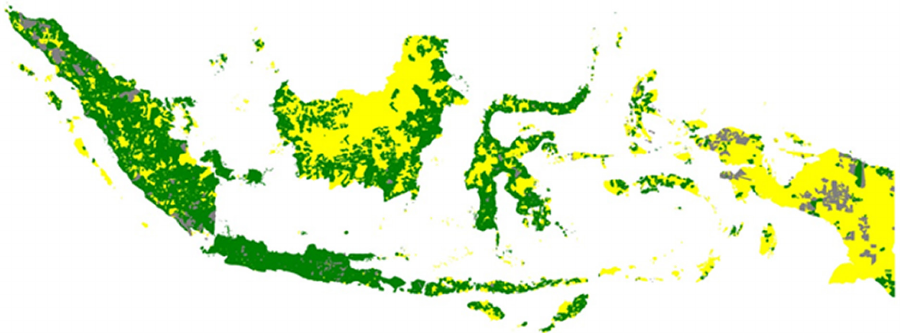

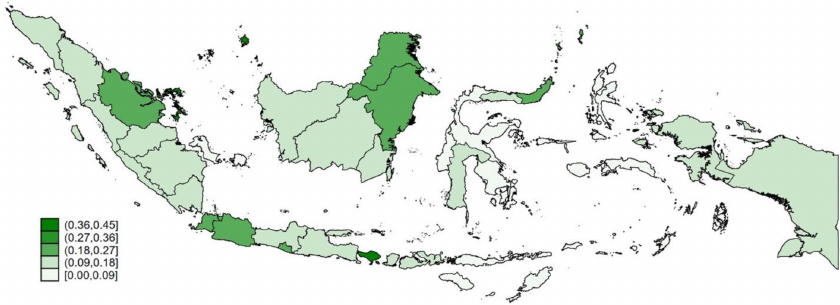

Figure 18. 3G and higher network coverage by village, Indonesia, 2018 ....................................35

Figure 19. Average price per 100 gigabytes of data (converted to US dollars), Indonesia ....... 36

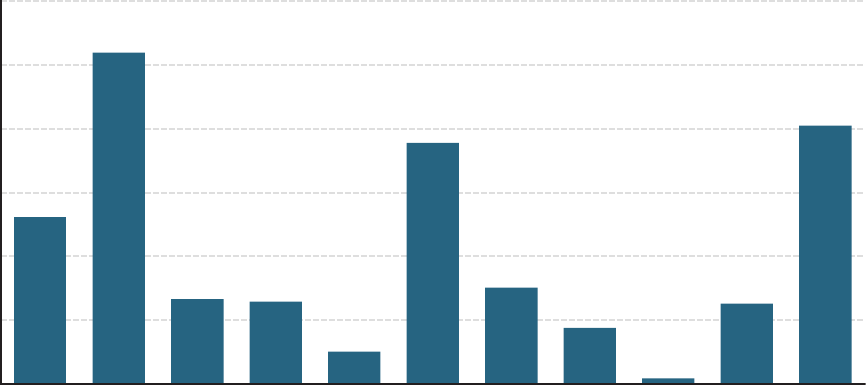

Figure 20. Number of BTSs by provider, Indonesia, 2016–2018 ................................................ 37

Figure 21. Median monthly profit (in US dollars) of branchless banking agents,

Indonesia versus benchmarks of comparator countries ..............................................................40

Figure 22. Percentage of adults making digital payments and perception of corruption,

Indonesia and comparator countries, 2017–2020 ..........................................................................41

Figure 23. Most-used payment methods, Indonesia, 2018 ............................................................ 43

Figure 24. Where users top up their e-money accounts, Indonesia, 2018 ..................................44

Figure 25. Convenience stores and supermarkets per 1,000 population,

Indonesia, 2018 ....................................................................................................................................45

Figure 26. Distribution of MSMEs by sector, Indonesia, 2019 ...................................................46

Figure 27. Reasons for not having a bank account,

by demographic characteristic (percentages) ..................................................................................48

Figure 28. Knowledge of financial terms, Indonesia, 2018 ..........................................................49

Figure 29. General trust level and digital payments, Indonesia and comparator

countries, 2017–2020 ..........................................................................................................................50

Figure 30. Bank account ownership and trust in financial service providers,

Indonesia, 2018 ..................................................................................................................................51

Figure 31. Consumer preferences on the cost of and trust in digital platforms .......................53

Figure 32. Ownership of bank savings account and income level, Indonesia, 2018 ...............57

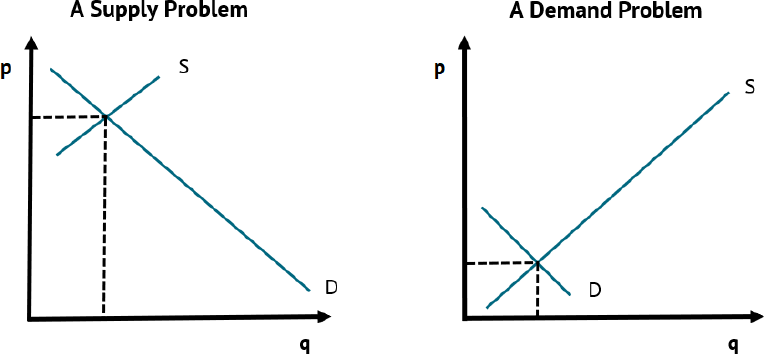

Figure A4.1. Distinguishing between supply and demand problems .........................................70

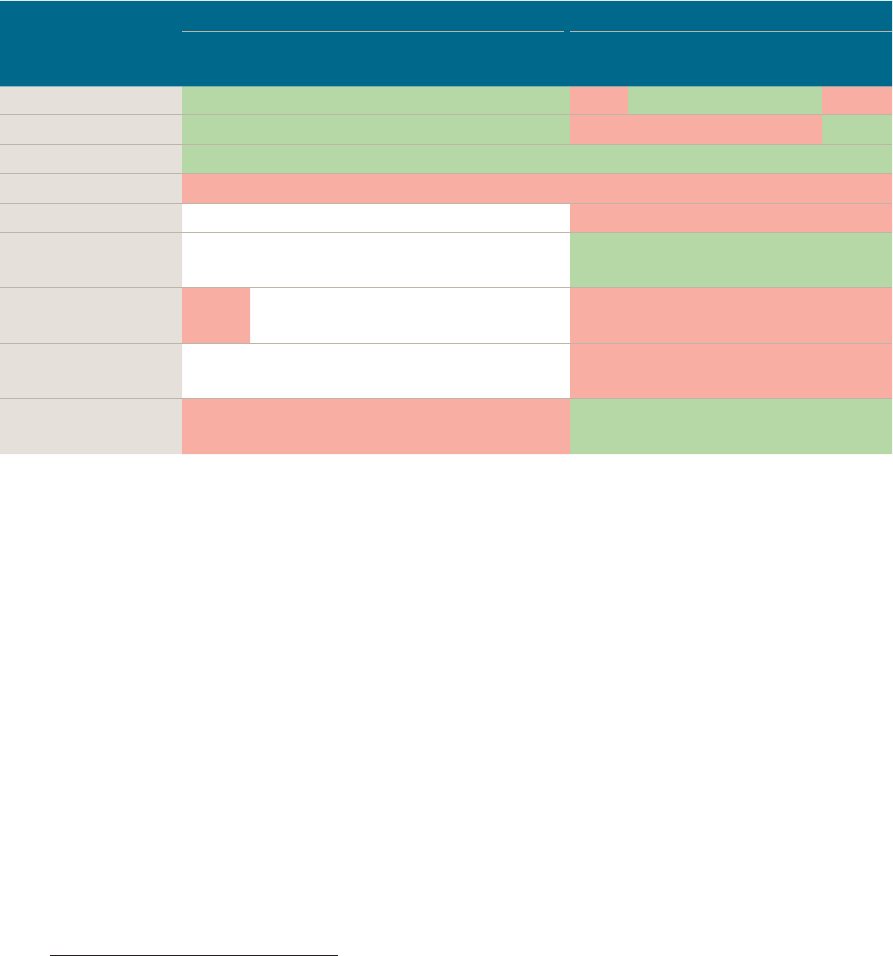

List of tables

Table 1. Major players in digital financial payment and store-of-value

services, Indonesia .............................................................................................................................11

Table 2. Requirements to open an account, Indonesia, 2020 ......................................................27

Table 3. Costs and time for KYC process ......................................................................................28

Table 4. Progress of Laku Pandai (BSA) program from June to December 2015 ....................31

Table 5. Market share of MNOs, Indonesia, 2018 ......................................................................... 36

Table 6. Recent cases of fraud, crime, and data breach involving

the digital economy, Indonesia, 2018–2020 ....................................................................................52

Table 7. Percentage of low-income people and ratio of PoS machines, Indonesia .................56

Table A1.1. E-money licenses, Indonesia, 2020 .............................................................................59

Table A2.1. Sources for provider-level cost and price data displayed in

Table 1 and Figures 6 and 9–12 ........................................................................................................60

Table A.3.1. Key regulations on digital financial services, Indonesia,

through October 2020 ........................................................................................................................67

Table A5.1. Sources of data displayed in Table 2, requirements to open an account ............... 71

Table A6.1. Sources of data displayed in Figure 19, average price

per 100 gigabytes of data ...................................................................................................................72

Table A7.1. Sources of data displayed in Table 6, cases of institution-level fraud ...................72

1

Abbreviations

ATM automated teller machine

BCA Bank Central Asia

BI Bank Indonesia

BNI Bank Negara Indonesia

BPD Bank Pembangunan Daerah

BRI Bank Rakyat Indonesia

BSA basic savings account

BTPN Bank Tabungan Pensiunan Nasional (National Pension Savings Bank)

BTS base transceiver station

DSP digital service provider

EDC electronic data capture (device)

FII Financial Inclusion Insights

GNI gross national income

GPN Gerbang Pembayaran Nasional (National Payment Gateway)

KYC know-your-customer

LKD Layanan Keuangan Digital (Digital Financial Services program)

MINFO Ministry for Communication and Informatics

MNO mobile network operator

MSMEs micro, small, and medium enterprises

OJK Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (Financial Services Authority)

P2P person-to-person

PODES Village Potential Statistics

PoS point-of-sale

QRIS Quick Response Indonesia Standard

2

Foreword

Financial inclusion, especially through digital means, is broadly regarded as a catalyst for

development and a driver of economic inclusion. While a large number of countries have

implemented policy changes to advance digital financial inclusion, results are mixed and

there is a substantial divide between countries that have achieved great success and those that

continue to lag behind.

To support policymakers’ eorts to improve the eectiveness of their financial inclusion

strategies, in early 2020 CGD published an analytical framework, A Decision Tree for Digital

Financial Inclusion Policymaking, that allows a systematic identification of the most problematic

constraints in country-specific settings. Many constraints can restrict financial inclusion, but

to dierent degrees. Therefore, the Tree aims at diagnosing which constraints are binding,

i.e., impeding significant usage of digital financial services. Without this kind of analysis,

gaps in financial inclusion strategies may persist and policymakers may focus attention on

non-binding constraints, obstacles whose solutions will not deliver significant improvements

unless other first-order impediments are addressed.

The Tree methodology uses a deductive top-down approach to analyze various potential

demand and supply causes (branches in the tree). An important feature of the analytical

framework is that it calls for analysis of the observed (or shadow) prices of digital financial

services to identify the most pressing (binding) constraints. Application of the methodology

involves benchmarking with a wide-ranging set of indicators, including aggregate and micro-

level statistics as well as survey data to reflect providers’ and consumers’ perceptions.

In this paper, Firman Witoelar, Teguh Yudo Wicaksono, and Carlos Mangunsong apply the

Tree methodology to the case of Indonesia.

The southeast Asia country has experienced a significant expansion of digital services

in recent years. E-commerce in particular has become increasingly popular, and many

innovations have taken place in this arena. However, the innovations and their benefits

have mostly advantaged individuals who were already financially included. Improvements

in eciency and digital financial services functionalities have not reached the substantial

population that remains excluded—over 50 percent of the adults, according to the most

recent estimates.

In their price analysis for digital payments and store-of-value services, Witoelar, Wicaksono,

and Mangunsong find that fees charged for e-wallet transfers are higher in Indonesia than in

comparable countries, indicating the presence of supply-side constraints.

Indeed, the authors find that an unlevel playing field between bank and non-bank providers

is a binding constraint. Regulations for non-bank providers ban their oering of cash-out

services restrict agent recruitment and impose higher know-your-costumer costs than those

applied to banks. They also reduce profitability and create substantial disadvantages to this

group of suppliers, which in many instances would be better suited to serve unbanked

populations. The authors also identify a coordination failure between suppliers and customers

3

as a binding constraint. The coordination problem manifests in the absence of a critical mass

of users, which further hinders agents’ profitability, limiting the oering of the services.

A deeper regional analysis shows the presence of additional binding constraints particular

to populations in remote and rural areas outside Java. Specifically, the low provision of

digital infrastructure and demand-side constraints such as customers’ perceptions of low

benefits from using digital financial services and lack of trust in providers are identified

as impediments whose solution would increase the potential of digital financial services

in Indonesia.

Indonesia’s digital financial services landscape is peculiar, with almost costless basic savings

accounts promoted by the government and a dynamic e-wallet market with multiple

providers, including those with non-traditional agents, such as GoJek drivers (equivalent to

Uber) that have many interactions with customers in urban areas. However, this promising

environment has continued to yield disappointing outcomes. Solving the binding and severe

constraints identified by Witoelar, Wicaksono, and Mangunsong could substantially benefit

the over 100 million Indonesians that remain financially excluded.

This is the last in a series of five policy papers that employ the Decision Tree methodology

that my colleagues and I developed to disentangle the most pressing constraints to financial

inclusion in countries where the low levels of inclusion are truly concerning and a hindrance

to prosperity. The other four papers study Ethiopia, India, Mexico, and Pakistan.

To learn more about this project, find these papers, and read additional material, please visit

cgdev.org/page/policy-decision-tree-improving-financial-inclusion.

Liliana Rojas-Suarez

Director of the Latin America Initiative and Senior Fellow

Center for Global Development

4

1. Introduction

In recent years, as countries have recognized the promise of increased use of modern

financial services, exemplified in studies such as those of Suri and Jack (2016), Claessens

(2006), and Beck, Demirguc-Kunt, and Peria (2006), national strategies for financial inclusion

were adopted, programs were rolled out, and new regulations were introduced to facilitate

financial inclusion. Indonesia, like many other middle-income countries around the world,

has likewise put a concerted eort into increasing financial inclusion.

To understand the limiting factors that still constrain financial inclusion, a large number of

studies, observational or experimental, have focused on particular determinants of financial

inclusion or addressed a specific constraint. Such research has often led to a long list of

policy or reform prescriptions, as many factors are indeed relevant for financial inclusion.

Dierent from previous studies, our paper takes a broader but also more nuanced approach

by looking at a large set of potential constraints to identify the binding ones. We use the

decision tree approach to the study of financial inclusion that was developed by Claessens

and Rojas-Suárez (2020), who in turn adapted the growth diagnostic approach introduced by

Hausmann, Rodrik, and Velasco (2005). The approach provides a framework to systematically

assess potential constraints on both the supply and the demand sides of the markets for

financial services, and to identify which of those constraints are binding. We use the decision

tree methodology to identify the most important factors that prevent improvement in the

adoption of two types of digital financial services in Indonesia—payments and store-of-

value services

1

—and focus on electronic money (e-money) products, which oer both

types of services, the latter through e-wallets. It is worth noting that e-money is provided in

Indonesia by both banks and nonbanks.

Our definition of financial inclusion is based on usage metrics; however, ownership (of a

device or account, for instance) may be used as a proxy

2

when usage data are not available. In

Indonesia, data from Financial Inclusion Insights (FII) surveys

3

(SNKI and FII 2019) show

that in 2018, around 45.5 percent of individuals 15 and older reported having owned and

used either a regular bank account, a basic savings account (BSA), or e-money (Figure 1).

4

1

We define digital payments (digitally stored value) as payments made (value stored) using any kind of digital

infrastructure and delivered using any of various channels such as a basic mobile phone, a smartphone, the

Internet, an ATM, or electronic data capture. Products for such purposes can come from various providers:

banks, nonbank providers, or e-commerce platforms.

2

This proxy, by definition, will overestimate financial inclusion, as some accounts will be open but dormant.

3

The FII 2018 survey (SNKI and FII 2019) was a nationally representative survey conducted by the country’s

National Council for Financial Inclusion in 34 provinces. The sample design was a stratified multistage cluster

sample of 6,695 adults in separate households, with urban-rural stratification.

4

“Regular banking accounts” here include regular savings accounts, demand deposit accounts, and other

products other than BSAs. The BSA is a low- or no-fee savings account with basic features, targeted to previously

unbanked populations. Electronic money (e-money) is a financial product whose record of funds or value

available to a consumer is stored digitally. E-money does not require a bank account. More precise definitions of

terms used in the analysis are provided in Section 2.

5

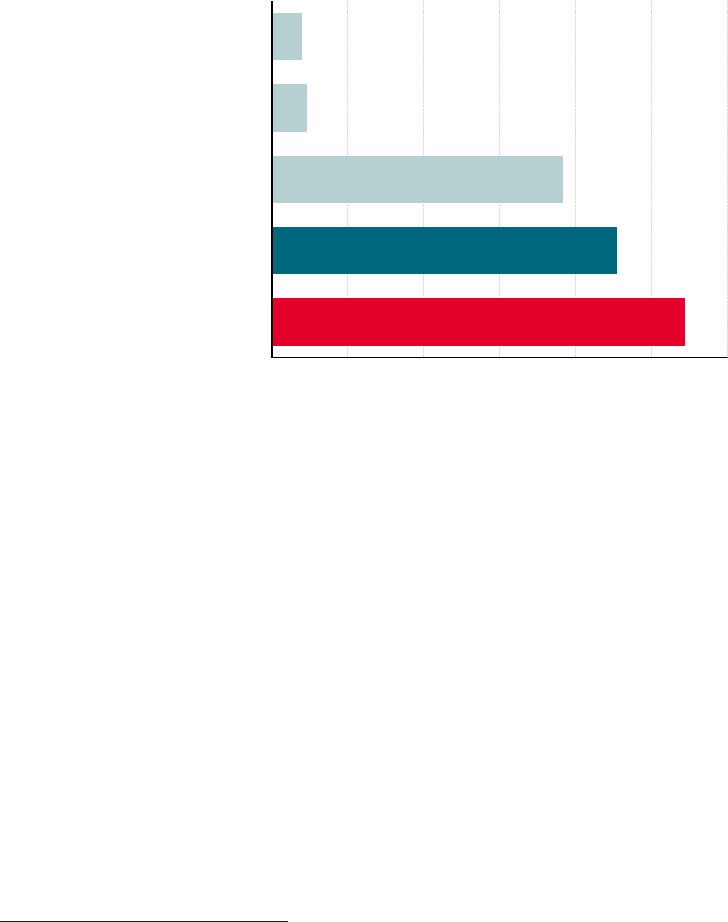

This means that more than half of the population reported never having used any of these

financial products. Thus, defining financial inclusion in terms of usage of these products

means that less than half of the adult population is financially included. Although there has

been remarkable growth in the percentage of the population with a bank account, from

35 percent in 2016 to 55 percent in 2018 (SNKI and FII 2019), there is still a significant

unbanked share of the population.

5

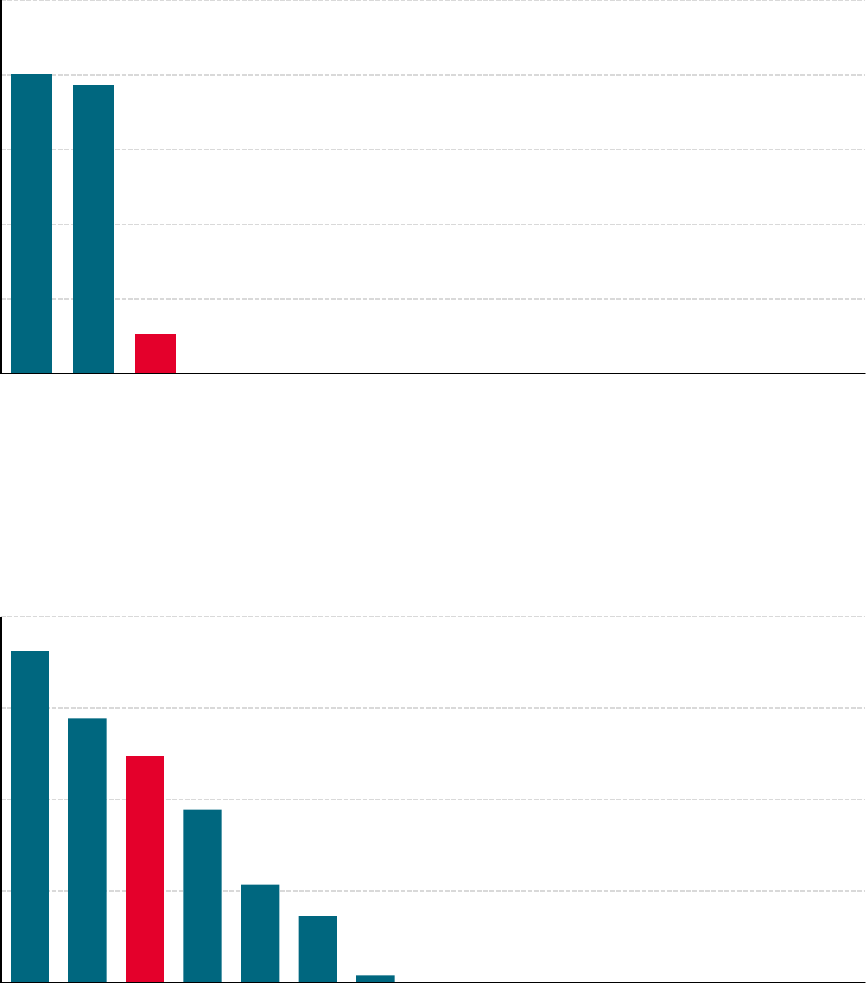

Figure 1. Formal financial products ever used, Indonesia, 2018

(self-reported use, percentage of adults 15+)

55%

46%

38%

5%

4%

0% 10% 20% 30% 40%50% 60%

Never used any

Any bank accounts or E-money

Regular bank accounts

E-money

Basic saving accounts

Source: Authors’ calculation using FII 2018 data (SNKI and FII 2019).

Note: The bars show the percentage of the adult population who reported owning and using each of the products.

Individuals may use more than one product.

The large proportion of the population that is financially underserved is striking, considering

that in the last five years Indonesia has made significant progress in extending financial

services. The use of regular bank accounts, for instance, experienced rapid growth. Between

2016 and 2018, the proportion of the adult population using a regular bank account

increased by 11.4 percentage points, although that brought it up to only 38.4 percent

(Figure 2), or approximately 50.3 million people, confirming that more than half of the adult

population is still financially excluded.

5

Note that the percentage shows ownership, not necessarily usage; usage numbers are closer to 45 percent.

A significant proportion of the new account owners in 2018 were social assistance beneficiaries, who started

to receive their social assistance via digital transfers that year.

6

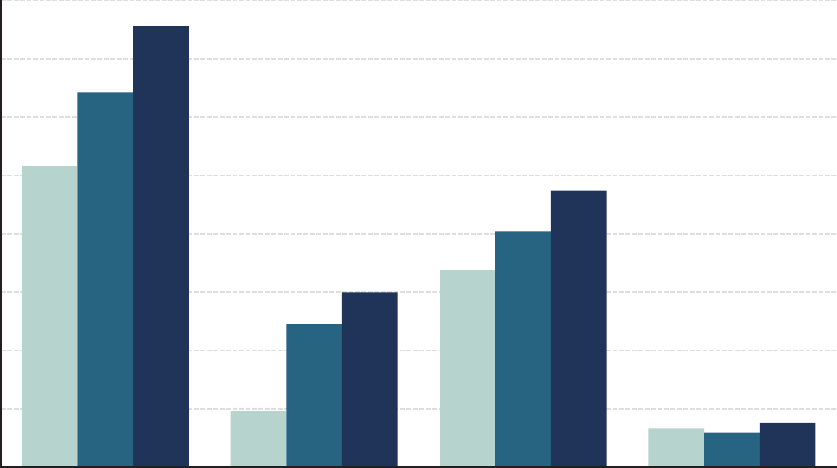

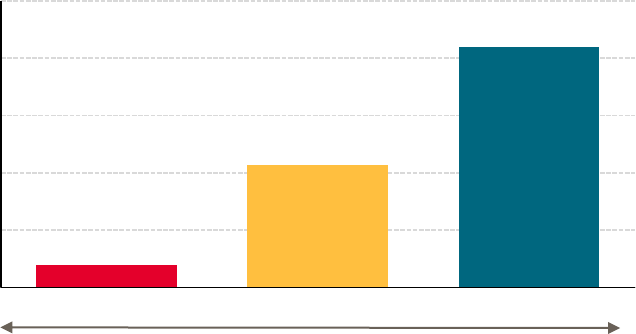

Figure 2. Use of regular savings accounts, BSAs, and e-money, Indonesia, 2014–2018

0.1%

22.2%

0.4%

24.1%

0.9%

2.7%

4.7%

38.4%

4.0%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

E-money Regular

bank

account

Regular

bank

account

Regular

bank

account

Regular

bank

account

E-money E-money E-money Basic

savings

account

2014 2015 2016 2018

Source: Authors’ calculation using FII 2018 data (SNKI and FII 2019).

Note: The bars show the percentage of the adult population who reported owning and using each of the products.

Individuals may use more than one product.

The introduction of digital financial services, particularly e-money, has been touted as a

vehicle to achieve the goal of financial inclusion. In 2014, the government of Indonesia

launched a national program to promote e-money, called Layanan Keuangan Digital (LKD),

which translates as “Digital Financial Services,” spearheaded by a number of state-owned

banks. E-money users are not required to have a bank account, and this early version of

e-money required only a feature phone.

6

These characteristics made it seem that LKD

had the potential to extend financial services to the unbanked. At around the same time,

regulators took a relaxed approach to e-money licensing, allowing a significant number of

e-money providers, mostly nonbank providers, to flourish. However, although the use of

e-money increased rapidly over the ensuing four years, overall usage remained low. Data show

that in 2018, only around 4.7 percent of the adult population used e-money (SNKI and FII

2019).

7

In this paper we investigate the reasons behind the poor performance of e-money

6

Around 46 percent of the adult population uses a smartphone, compared with 70 percent who own a feature

phone. Nevertheless, even among smartphone users, e-money usage is low (9.5 percent of smartphone owners)

(Moorena et al. 2020, using data from SNKI and FII 2019). Our calculation, using data from the same survey,

shows that 38 percent of the financially excluded adult population use a smartphone. In 2019, four state-owned

banks and a state-owned telecommunication company, through a subsidiary, launched a new e-money product

called LinkAja to replace the e-money products introduced through the LKD program. LinkAja requires a

smartphone.

7

Based on a slightly dierent definition of mobile money use, which included online purchases and

bill payments, the World Bank’s Global Findex 2017 found usage in Indonesia to be around 6 percent

(Demirguc-Kunt et al. 2018).

7

services in Indonesia, which can shed some light on the causes of the overall low levels of

financial inclusion in the country.

While innovations in digital financial services are being developed rapidly—for payments,

remittances, and credit—it seems that many of those who previously were not served by

banks still cannot exploit the benefits of digital financial services. Instead, there are signs that

the utilization of digital financial services has been more concentrated among the already

financially included population.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we further discuss the landscape

of digital financial services in Indonesia to provide context for the paper. The section

presents the digital financial products that we are going to analyze and provides more precise

definitions of a number of terminologies that we discuss in the paper. It also provides

an overview of the state of digital finance, focusing on e-money. Section 3 describes the

Claessens and Rojas-Suárez (2020) methodology of the decision tree. In Section 4, we

undertake a price analysis that compares the fees charged for digital financial services oered

in Indonesia with those in other selected countries; this analysis provides initial insights as

to whether the binding constraints are on the supply or the demand side of the decision

tree. In Sections 5 and 6, we assess each of the potential constraints aecting, respectively,

the supply of and the demand for digital financial services, in order to determine which are

binding. Section 7 provides key lessons and conclusions.

2. The digital financial system landscape:

providers and products

The explosion of digital financial services in recent years has brought with it a number of

new providers that oer dierent services, such as payments, loans, and insurance, either

individually or as a bundle through specific products (e-money and a BSA, for instance). In a

market that is still innovating, the lines between the dierent types of products are sometimes

blurred, and there is not always a clear-cut definition that is uniform.

This paper focuses on analyzing the use of digital financial products for payment and store-

of-value services—in particular, the digital financial product that may have the highest

potential to expand financial inclusion: e-money. This product has both payment and store-

of-value functionalities, though both are somewhat limited. Given the fast-growing adoption

of e-money, even among those who do not own and use a bank account, there are reasons to

believe that if some constraints were removed, its potential could be unleashed to reach the

unbanked population.

Electronic money, or e-money, is a record of funds or value available to a consumer that

is stored digitally, whether on a microchip, a prepaid card, a mobile phone, or a computer

system. An e-money account belonging to a customer is called an e-wallet. Transactions

can be done via a basic mobile phone, a smartphone, a card, an ATM, or an electronic data

capture (EDC) device, and the provider of the service can be a bank, a nonbank financial

8

institution, a mobile network operator (MNO), or an e-commerce platform.

8

As discussed

later, many forms of e-money oered in Indonesia lack some important e-money features

that are available in many other countries, most importantly the cash-out feature.

9

Although

the main functionality of e-money is making payments, by allowing users to have a balance, it

also oers store-of-value services, albeit for limited amounts.

10

As in many other countries, e-money in Indonesia does not require a bank account and is

issued by both banks and nonbanks. However, unlike in other countries such as Kenya,

where mobile money has flourished using feature phones, in Indonesia, e-money providers

typically issue server-based e-money that requires a smartphone,

11

and the market continues

to move toward requiring these devices.

12

In Indonesia, the dramatic increase in transactions

relying on e-money was spurred by e-commerce, which established e-money as an integral

part of the big tech platform ecosystem.

13

One of the most prominent providers is GoJek,

a ride-hailing service, which established GoPay, an e-money that was initially intended to

let customers pay their drivers within the GoJek network.

14

In recent years, e-money has

continued to grow, particularly through nonbank providers.

8

Most recently, one of the largest chains of convenience stores in Indonesia, Indomaret, issued its own server-

based electronic money, called iSaku, that can be used for payments, transfers within the network, and purchases

at participating merchants.

9

A few other countries have similar restrictions on cash-out services. In India, for example, only providers with a

banking license can provide cash-out services.

10

Electronic money, as discussed in our analysis, includes both server-based and card-based e-money. Card-based

e-money is similar to a debit card, in which the value is stored in a chip that is embedded in the card. Users can

access their e-wallet by using the card. E-money issued by banks in Indonesia typically uses this technology and

requires agents to use EDC devices. Server-based e-money typically does not require a card; instead, users access

their e-wallet using a mobile phone. The value is stored, recorded, and managed centrally on the server of the

e-money provider. This type of e-money allows customers to transfer money through smartphone other Internet-

based applications.

11

Several attempts to develop MNO-based mobile money failed to take o. As discussed in the analysis, part of

the failure can be attributed to an uneven playing field in the regulations that puts MNOs at a disadvantage.

12

For example, when a consortium made up of state-owned banks and the state-owned MNO introduced its

own e-money called LinkAja in 2019, it chose to use server-based e-money that requires a smartphone to replace

the feature phone–based e-money previously issued. Before establishing LinkAja, each of the state-owned banks

had its own e-money, launched under the LKD program in 2014. The state-owned MNO, Telkomsel, oered the

mobile money called T-Cash. Indosat, the second-largest MNO in Indonesia, exited the mobile money market in

2017 after three years. The third-largest MNO, XL Axiata, shut down its mobile money, XL-Cash, in 2020. We

discuss the barriers faced by MNOs in entering the e-money market in Indonesia in Box 3. Except for the recent

market reentry of Indosat with a feature phone–based mobile money product called IMkas, no major e-money is

currently feature phone–based.

13

The development of e-money in Indonesia seems to follow the mobile financial service model of China,

whereby large tech platforms such as e-commerce companies set up their own payment systems to enable their

customers to pay for their services (Demirguc-Kunt et al. 2018). For example, the e-commerce giant Alibaba

provides its own payment system, Alipay, and customers in China use an Alipay smartphone app to access their

accounts. Customers in Indonesia use a GoJek app to access their GoPay accounts. In contrast, in Kenya, mobile

financial services are oered mainly by MNOs, and the accounts do not need to be linked to a bank account.

14

Over time, as GoJek expanded its business model, including food delivery and logistics, it began allowing GoPay

to be used for person-to-person and person-to-business transactions. GoPay has now transformed itself into a

significant electronic payment service that can be used to conduct transactions both within and outside the GoJek

ecosystem, including transactions with brick-and-mortar stores.

9

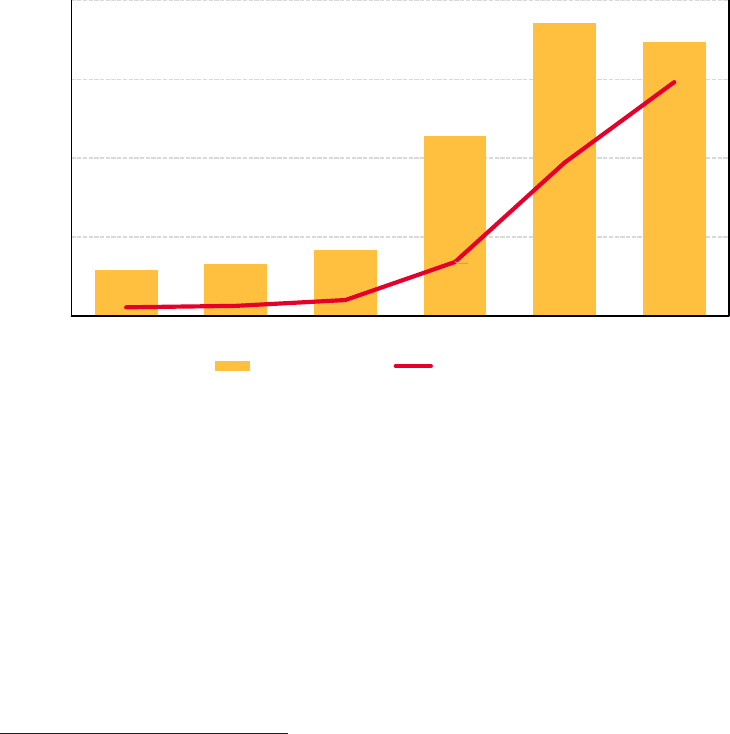

This solid growth of e-money providers can be attributed to the regulatory support of Bank

Indonesia (BI). In 2020, BI approved 51 e-money licenses (see Appendix 1), an increase of

31 percent compared with 2019, when only 39 companies were approved to operate e-money.

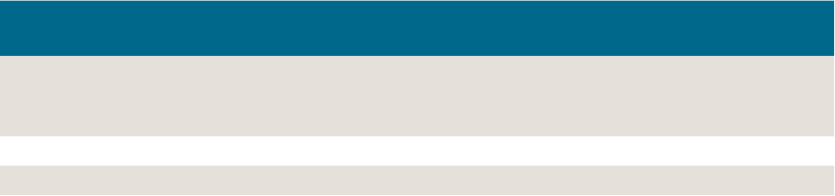

Figure 3 shows the rapid increase of transactions using e-money, in terms of both volume

and value. Note that the figure includes e-money transactions using both server-based and

card-based e-money. Finally, it is plausible that the growth reflects more an expansion at

the intensive margin—that is, a subset of the population using more e-money—rather than

at the extensive margin—that is, an increase in transactions due to more individuals using

e-money.

15

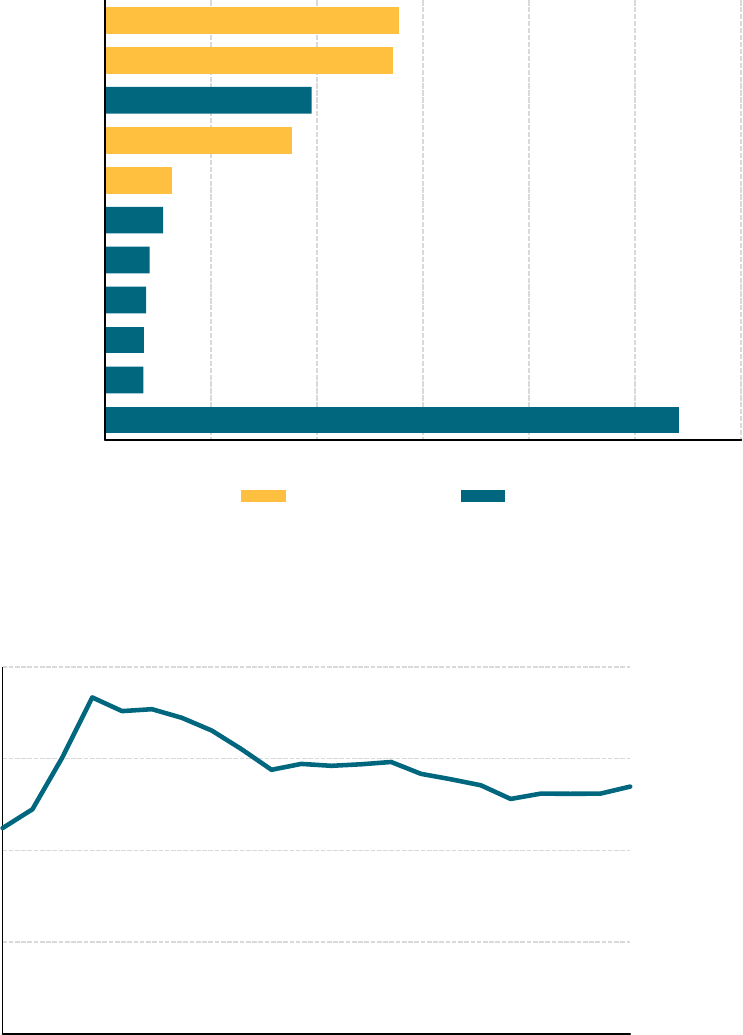

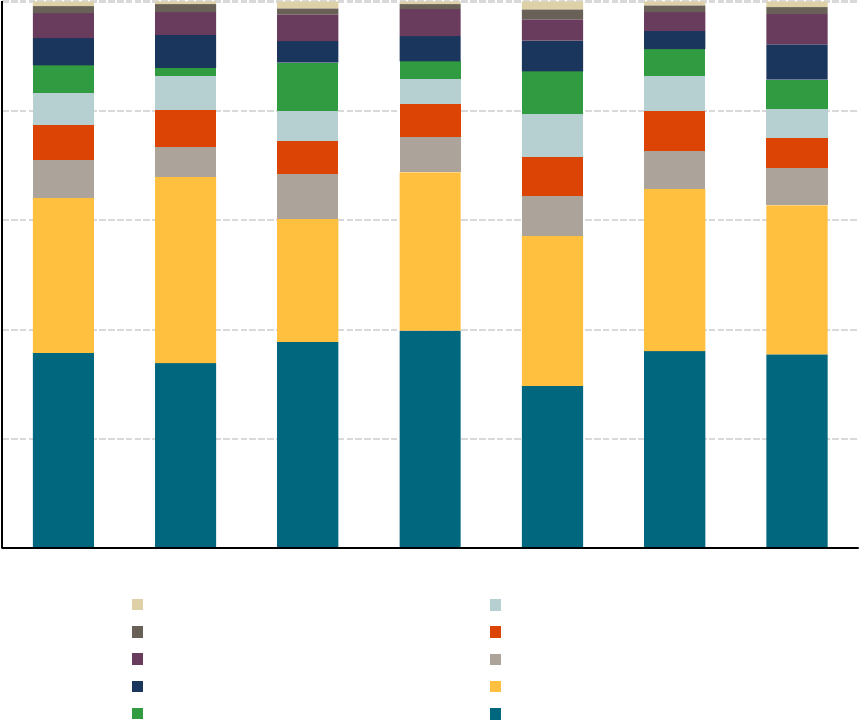

Figure 3. E-money transaction volume and nominal value as percentage

of ATM and debit card transactions, Indonesia, 2015–2020

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

2015

0.11% 0.13%

0.20%

1.94%

2.96%

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

% Volume (LHS) % Nominal value (RHS)

0.68%

Source: BI (2021b).

Note: Percentage of volume is on the left-hand side (LHS) axis and percentage of nominal value is on the right-

hand side (RHS) axis. Labels on the red line indicate the nominal value of transactions in billions of USD PPP.

With regard to other digital payment and store-of-value services, in 2018, according to the

FII 2018 survey (SNKI and FII 2019), around 36 percent of the adult population owned an

ATM card,

16

which is close to the percentage of individuals with a bank account (regular and

BSA combined). In contrast, the survey showed that only around 4.7 percent of the adult

15

Publicly available data do not reveal the number of users. Thus, it is dicult to determine whether an increase

in the number of accounts and transactions means a proportional increase in the number of users.

16

Banks in Indonesia typically do not oer checking accounts (also called “current accounts”) to regular savings

account customers. The features of checking accounts are targeted to businesses and certain individuals with high

transaction needs, and in fact, opening a checking account requires proof of a business license. Thus, checking

accounts are very uncommon, and the tradition of making (digital) payments with a card seems to be well

established.

10

population used e-money.

17

Among those who said they had used it, only 60 percent reported

having “used it regularly in the past month,” although its use has been increasing rapidly.

18

In terms of usage, ATMs are also the most important channel used to withdraw or deposit

money (SNKI and FII 2019). The survey also shows that 85 percent of individuals with a

bank account withdrew money at least once in the past six months, and around 89 percent

withdrew money through an ATM (Figure 4).

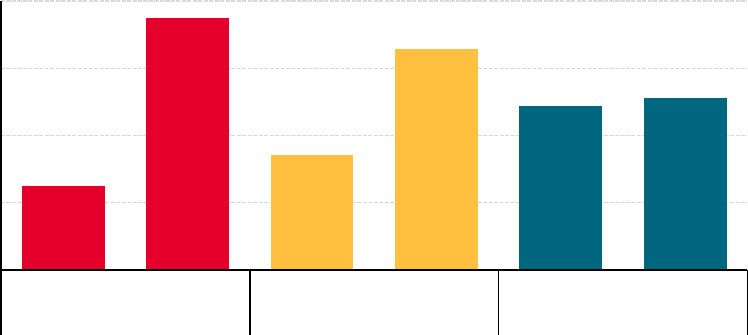

Figure 4. Method of making account withdrawals and deposits, Indonesia, 2018

85%

19%

89%

8%

54%

60%

48%

15%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Average Teller ATM Agent Average TellerATM Agent

Any Withdrawal Any Deposit

Source: FII 2018 survey (SNKI and FII 2019).

Table 1 shows the major providers of digital financial services in Indonesia and the services

they oer. Three of the banks listed in the table—Bank Mandiri, Bank Negara Indonesia

(BNI), and Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI)—are state-owned banks. One of the nonbank

digital service providers (DSPs) listed, LinkAja, is owned by a consortium of state-owned

banks—Mandiri, BNI, BRI, and Bank Tabungan Negara (BTN)—and the state-owned

MNO, Telkomsel. The table shows some key dierences between the digital payment services

oered by banks and nonbank DSPs, and whether they charge users for these services.

Nonbank DSPs’ services are restricted to payments, transfers between domestic accounts,

17

Based on a slightly dierent definition of mobile money use, which included online purchases and

bill payments, the World Bank’s Global Findex 2017 found usage in Indonesia to be around 6 percent

(Demirguc-Kunt et al. 2018).

18

Payment statistics from BI (2021b) reported that between 2018 and 2019, ownership of app-based and card-

based e-money accounts increased by 74.8 percent. The number includes accounts owned by businesses and

individuals, and each group can have multiple e-money accounts, so the number is not directly comparable to the

percentage of e-money users extracted from the survey.

11

and deposits (cash-in services), while banks also allow users to withdraw money (cash-out)

and conduct international transfers, with some restrictions.

19

Table 1. Major players in digital financial payment

and store-of-value services, Indonesia

Service DSPs Banks

GoJek OVO LinkAja Dana ShopeePay BCA Mandiri BNI BRI CIMB

Niaga

Open account Free Free Free Free Free Paid Free Free Free Paid

Annual admin Free Free Free Free Free Paid Paid Paid Paid Free

Internal transfer Free Free Free Free Free Free Free Free Free Free

External transfer Paid Paid Paid Paid* Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid

International transfer N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid

Withdraw from own

ATM

N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A Free Free Free Free Free

Withdraw from other

ATM, domestic

Paid* N/A N/A N/A N/A Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid

Withdraw from other

ATM, international

N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid

Top up card or

account

Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Free Free Free Free Free

Source: Compiled by authors from banks’/providers’ websites (see Appendix 2).

Note: BCA = Bank Central Asia; N/A = not applicable. * GoJek has only started recently to allow ATM-based

withdrawal in collaboration with BCA.

20

To summarize, in terms of reaching the goal of financial inclusion, e-commerce–based

e-money, as well as bank-issued e-money such as LinkAja, has the potential to introduce

digital payment services to a substantial segment of the adult population who have

smartphones, some of whom do not currently use bank accounts or e-money—around

31.7 percent of financially excluded adults own smartphones, according to our estimate

from FII 2018 data (SNKI and FII 2019).

Appendix 3 completes the landscape section by discussing the key stakeholders and

regulations that aect digital financial inclusion in Indonesia.

19

E-money issued by banks can be cashed out under some conditions. Users must be registered, and registration

requires additional know-your-customer documents. Most banks allow only agents that meet certain criteria—

usually measured by their performance—to provide cash-out services. Nonbank DSPs must apply for a separate

permit to oer cash-out services. Section 4 discusses more extensively the regulations governing this issue.

20

Recently, verified and premium Gopay users can withdraw funds from ATMs if have BCA accounts,

per Gojek’s ocial statement accessed on July 19th 2021, from: https://www.gojek.com/blog/gopay/

cara-tarik-tunai-tanpa-kartu-bca/.

12

3. Methodology: identifying binding constraints

using the decision tree approach

This section discusses the application of the decision tree methodology to analyze binding

constraints on the use of digital payment and store-of-value services. The methodology

follows Claessens and Rojas-Suárez (2020), adapting the growth diagnostics approach

developed by Hausmann, Rodrik, and Velasco (2005) and Hausmann, Klinger, and Wagner

(2008). The details of the methodology are further described in Appendix 4.

21

As previously noted, the goal of this paper is to identify the binding constraints on financial

inclusion, focusing on digital payment and store-of-value services. The binding constraints

are the main limiting factors that are currently impeding the development of financial

inclusion in the country, and whose relaxation would yield substantial improvements in

inclusion. The decision tree starts by acknowledging that the use of digital payment services

is determined by supply and demand factors. Under each branch of the tree, the first-tier

nodes represent factors that, based on existing theories and empirical literature, are identified

to be constraints on the supply of and the demand for digital financial services. Again, based

on the existing literature, each of these factors is known to be determined or aected by

additional factors, which are listed in the second-tier branches.

We see that on the supply side, the three factors that are listed as potential constraints

are the market structure of banks and DSPs, insucient digital infrastructure, and low

appropriability of returns (see Figure 5). The three factors that can potentially constrain the

demand for digital payment and store-of-value services are perception of low benefits of

usage, low trust in providers, and income and geographical factors.

The market structure of providers may limit the availability of digital payment and store-

of-value products to only a narrow segment of the population. For example, limited

competition can prevent providers from oering a wide range of services to large segments

of the population. Increased competition has the potential to encourage providers to expand

their services at the extensive margins as well as improve their services to existing users.

Market structure is also determined by the regulatory environment—when the regulations

treat alternative providers of similar products dierently, it is likely that the disadvantaged

providers may not be able to provide services at prices that are low enough to attract users.

Insucient digital infrastructure, in terms of both quantity and quality, may prevent

providers from reaching the population segments that will benefit from financial inclusion.

Low availability of reliable digital infrastructure and high prices for usage of this

infrastructure indicate constraints on the supply side, which can be a result of several factors,

including limited competition and entrenched lack of interoperability between providers.

21

Claessens and Rojas-Suárez (2020) provided two dierent decision trees—one for payment and transfer

services and one for store-of-value services. The main dierence between the two trees is the presence of two

additional nodes in the store-of-value services tree that are not in the other tree, namely, financial literacy and

macroeconomic instability.

13

Figure 5. Decision tree for payment and store-of-value digital financial services

Unleveled playing

field, inadequate

rules

(also related to low

perception of

benefits)

Poor

institutional

quality and

governance

Low

appropriability

of returns

Low income

Low trust

in providers

Limited

competition

oligo/monopoly

Entrenched

lack of

interoperability

Distortionary

taxes and

other

policies

Limited demand for payment and

store of value services

Limited provision of payment and store of value services

by banks and DSPs to large segments of the population

Perceived low

or no benefits

of usage

Supply & Demand

Insufficient

or poor

private

digital

infrastructure

Problems

identifying

customers

Coordination

failures (e.g.,

critical mass)

Too costly to operate

privately, given

geo/demography

Consumer

insecurity

Lack of

awareness of

financial

products

Market

structure

of banks

Market

structure of

telecoms

and other

DSPs

Macroeconomic

instability

Source: Claessens and Rojas-Suárez (2020).

The third supply-side factor that can constrain the supply of digital payment as well as

store-of-value services is the low appropriability of returns. Providing digital services to the

unbanked population may have high social returns. However, providers may find it dicult

to appropriate these returns, and low private returns may discourage providers from entering

the market. The diculties in appropriating the returns can be due to four factors, which

constitute the second-tier nodes of the supply branch. First, poor quality of institutions

and governance may hinder the ability of providers to appropriate returns. Second, there

could be distortionary policies or taxes that reduce profits and discourage providers from

participating. Third, there may be diculties in verifying the identity of customers. This

know-your-customer (KYC) issue, both necessary as internal provider policy and imposed

by regulations, may increase costs for both providers and customers. Finally, there could be

coordination failures between the supply side and the demand side whereby, on one hand,

providers are discouraged from entering the market due to the lack of a critical mass of

users, and on the other hand, large segments of the population are reluctant to take up digital

payment or store-of-value products due to lack of either agents that can provide the services

or counterparts to transact with.

Returning to the first-tier branch on the demand side, the first factor that can limit demand is

the perception that using digital products carries low or no benefit. For instance, to continue

with the example of coordination failure above, when there are only a few agents available to

provide digital payment or store-of-value services, customers may not find it worthwhile to

take up these products. Lack of awareness regarding available financial products also causes

a perception of low or no benefits.

14

The next factor that can aect demand is low trust in providers, which makes customers

less likely to demand the products. Low levels of trust can stem from past experience

with fraud, other sources of consumer insecurity, or macroeconomic instability. Because

households’ usage of financial services for store-of-value purposes is usually associated with

larger monetary amounts than their usage for making payments, consumer insecurity and

macroeconomic instability may be more important factors in the decision tree for store-of-

value services than for payments.

Finally, the last factors that can constrain demand are low income and geography. For the

segment of the population with very low incomes, even low prices of digital payment or

store-of-value services can prove to be prohibitive. In countries with large geographical

diversity, like Indonesia, there may be pockets of remote areas where high transaction costs

restrain customers from demanding the services.

We apply the four principles proposed by Hausmann, Rodrik, and Velasco (2005), when

possible, to each branch and sub-branch of the tree. The first principle is to consider the

(shadow) price of the services to distinguish between supply and demand constraints, as low

usage of services can be a result of either or both. High service fees indicate that providers

are willing to provide only a limited quantity of services, and that only for a high price. When

the price is high and the quantity of digital finance usage is low, then the constraint is on the

supply side. On the other hand, when both the price and the usage are low, it is very likely

that the binding constraint is on the demand side.

The second principle indicates that any movement in a constraint that is binding should

produce significant movements in the objective function; that is, when a binding constraint

is relaxed, usage of digital finance will likely increase significantly. The third principle states

that if agents in the economy attempt to overcome or bypass a constraint, that constraint is

probably binding. Any evidence of agents who are willing to incur additional risks or costs in

order to circumvent a constraint provides an argument that the constraint is binding. Finally,

the fourth principle suggests that agents who are less aected by a binding constraint will be

more likely to thrive, and vice versa.

To proceed with the analysis, the first step we take is to look at prices of the relevant digital

financial services for which data are available (Section 4). The price analysis will oer key

signals that guide us in the search for binding constraints. We will then analyze each branch

of the decision tree, both on the supply side (Section 5) and on the demand side (Section 6),

using a set of indicators.

15

4. Prices for digital payment and store-of-value services

We start our analysis by examining the prices that are relevant for usage of digital payment

and store-of-value services. We begin by looking at fees charged for using an ATM, which

would be a good benchmark for cross-country comparisons, given the widespread use of

ATMs not only in Indonesia but also in other countries. We then look at fees charged for use

of an e-wallet, including external transfer fees and withdrawal fees. It is worth noting that

ATM fees are also relevant for e-money, as many users may withdraw their funds via ATM.

Although we focus on e-money, it may be useful to compare this product with what may

currently be the most popular digital payment product in Indonesia, namely, ATM cards

(or debit cards in general). Indeed, before the advent of e-money in Indonesia, payments

using an ATM card were the only digital payments available. Based on the data from SNKI

and FII (2019), around 36 percent of the adult population owned an ATM card in 2018,

which is close to the percentage of individuals with a bank account (regular and BSA

combined). ATMs are also the most popular digital financial services used to withdraw

or deposit money. From the same data, around 85 percent of individuals with a bank

account withdrew money at least once in the past six months, and around 89 percent of

them withdrew money using ATM cards (SNKI & FII, 2019). ATM cards are arguably also

popular in other countries, a fact that allows us to assess the relative prices of ATM cards in

Indonesia and other countries. Benchmarking with other countries in ATM card prices and

usage gives us a perspective on how the price of digital financial services aects the use of

such services.

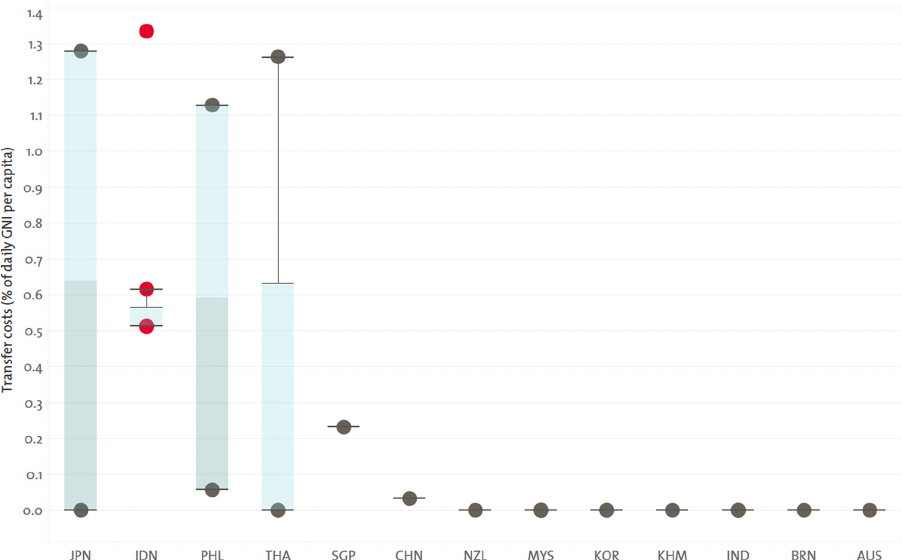

We begin by looking at the cost associated with the use of an ATM. Figure 6 shows the

average ATM fees to withdraw money from a regular savings account in Indonesia and in

selected other countries as a percentage of daily GNI per capita (converted to US dollars

and adjusted for purchasing power parity). The graphs show that while the fee is lower in

Indonesia than in China, Laos, and Vietnam, it is still higher than in neighboring Malaysia, the

Philippines, and Singapore. Note that while this fee tells us the market price of withdrawing

money from an ATM, there are important indirect costs—such as access to the ATM

itself, typically measured as the distance to the closest ATM or the number of ATMs per

population—that determine the shadow price of ATM services. These nonpecuniary costs

are relevant for both savings account users and e-money users who wish to withdraw cash

from an ATM. Note that because e-money issued by nonbank DSPs does not have a cash-

out feature, users of these types of e-money need to have a bank account to access an ATM.

The growth in the penetration of ATMs in recent times is likely to have lowered these

indirect costs. The number of ATMs—accessible by people with a regular savings account

and by those whose BSAs come with ATM cards—grew from around 13 per 100,000

population in 2010 to 55 in 2018 (World Bank 2020). Further, the interoperability between

dierent ATMs that now allows virtually any bank card to be able to withdraw from any

ATM is also growing.

16

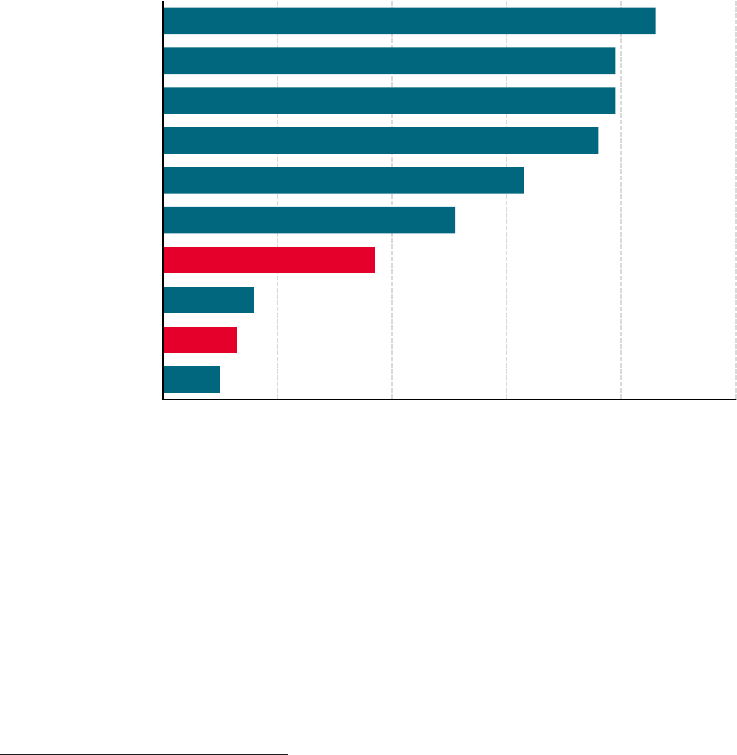

Figure 6. Average bank ATM withdrawal fee as percentage of daily GNI per capita,

2020, Indonesia and selected comparator countries

2.6%

5.2%

1.3%

1.3%

0.5%

3.8%

1.5%

0.9%

0.1%

1.3%

4.1%

Cambodia

China

Indonesia

Japan

Korea

Lao PDR

Ne

w Zealand

Philippines

Singapore

Thailand

Vietnam

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

6%

Source: Compiled by authors from providers’ websites (see Appendix 2).

However, we can see in Figure 7 that the number of ATMs per population is still lower

in Indonesia than in a number of neighboring countries, and it corresponds to a lower

percentage of the population making digital payments.

In terms of geographical disparity, Figure 8 shows that the number of points of service for

regular bank accounts and BSAs—including banks, ATMs, and branchless banking agents—

is uneven across the country, implying that the costs are even higher for populations outside

Java and other urban centers.

17

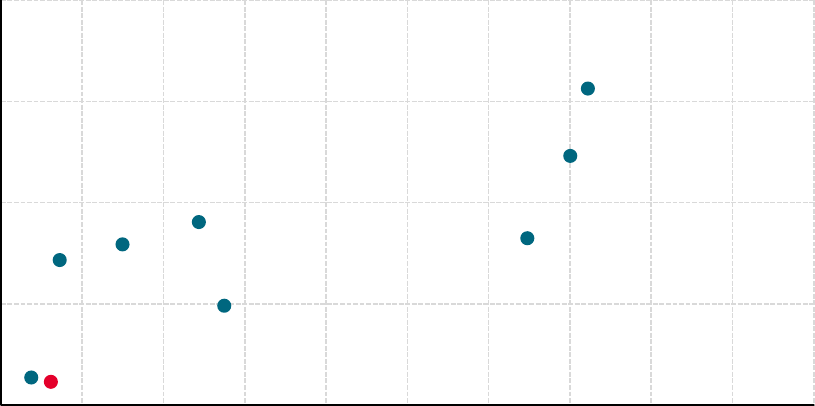

Figure 7. ATMs per population and usage of digital payments,

Indonesia and selected comparator countries, 2020

CHN

IDN

IND

KHM

MMR

MYS

NZL

PHL

SGP

THA

VNM

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

020406080100 12

0

Made digital payments in the past year

(% age 15+)

Automated teller machines (ATMs) (per 100,000 adults)

Source: World Development Indicators (World Bank 2020) and Findex 2017 (Demirguc-Kunt et al. 2018).

Note: India, Cambodia, and Viet Nam are the correct order of countries sorted in ascending order of ATM per

100,000 adults.

Figure 8. Number of points of service for BSAs, including banks, ATMs,

and branchless banking BSA agents, Indonesia, 2018

Source: FII 2018 (SNKI and FII 2019).

18

For e-money users, one of the most relevant prices is the e-wallet transfer fee. Figure 9 shows

the cost of transferring funds from a bank account or from an e-wallet issued by a nonbank

DSP in Indonesia. The cost shown represents the fee that a user must pay to transfer funds

to an account outside the same bank (for bank-issued e-money) or e-commerce platform.

Note that for nonbank DSPs the transfer is always to a bank account and not to an e-money

account in a dierent platform. The figure shows that for most nonbank DSPs except

LinkAja, transferring funds outside the platform is cheaper than from a bank account.

Figure 9. External transfer fees for e-wallets of selected banks and e-money providers

as percentage of daily GNI per capita, Indonesia, 2020

1.3% 1.3% 1.3% 1.3% 1.3% 1.3%

0.6%

0.5% 0.5% 0.5% 0.5% 0.5% 0.5%

0.0%

0.3%

0.6%

0.9%

1.2%

1.5%

OVO (IDN)

Mandiri (IDN)

CIMB (IDN)

BRI (IDN)

BNI (IDN)

BCA (IDN)

Bank

Link Aja (IDN)

Shopeepay (IDN)

OVO Premier (IDN)

Gopay Plus (IDN)

Gopay (IDN)

Dana Premium (IDN)

Dana (IDN)

E-Wallet

Source: Compiled by authors from providers’ websites (see Appendix 2).

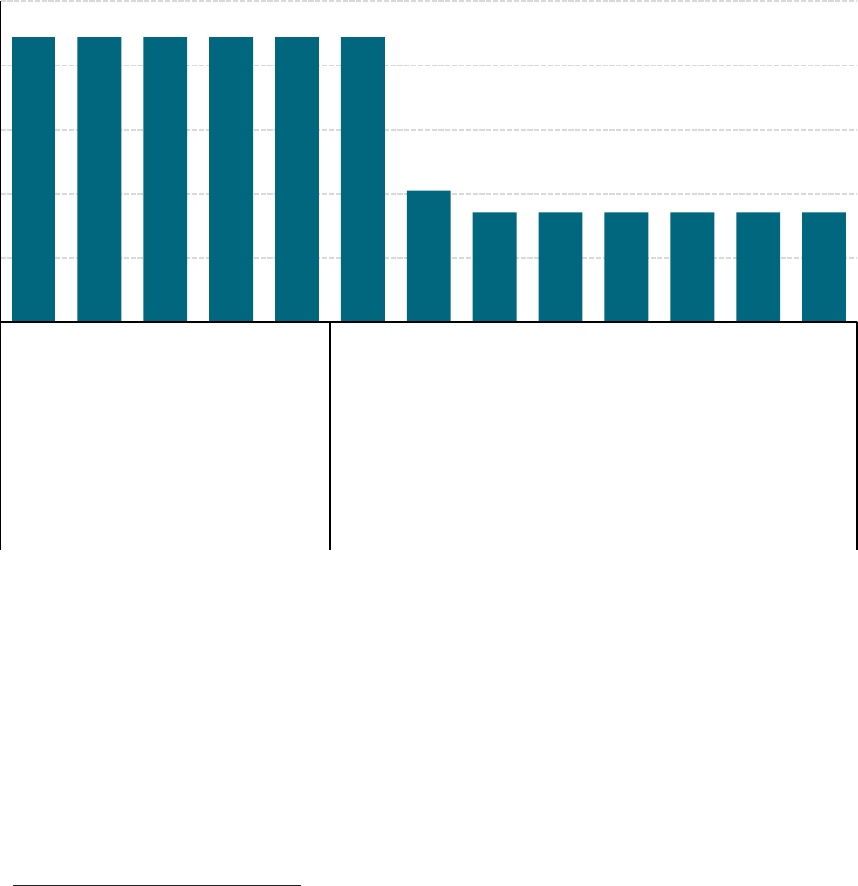

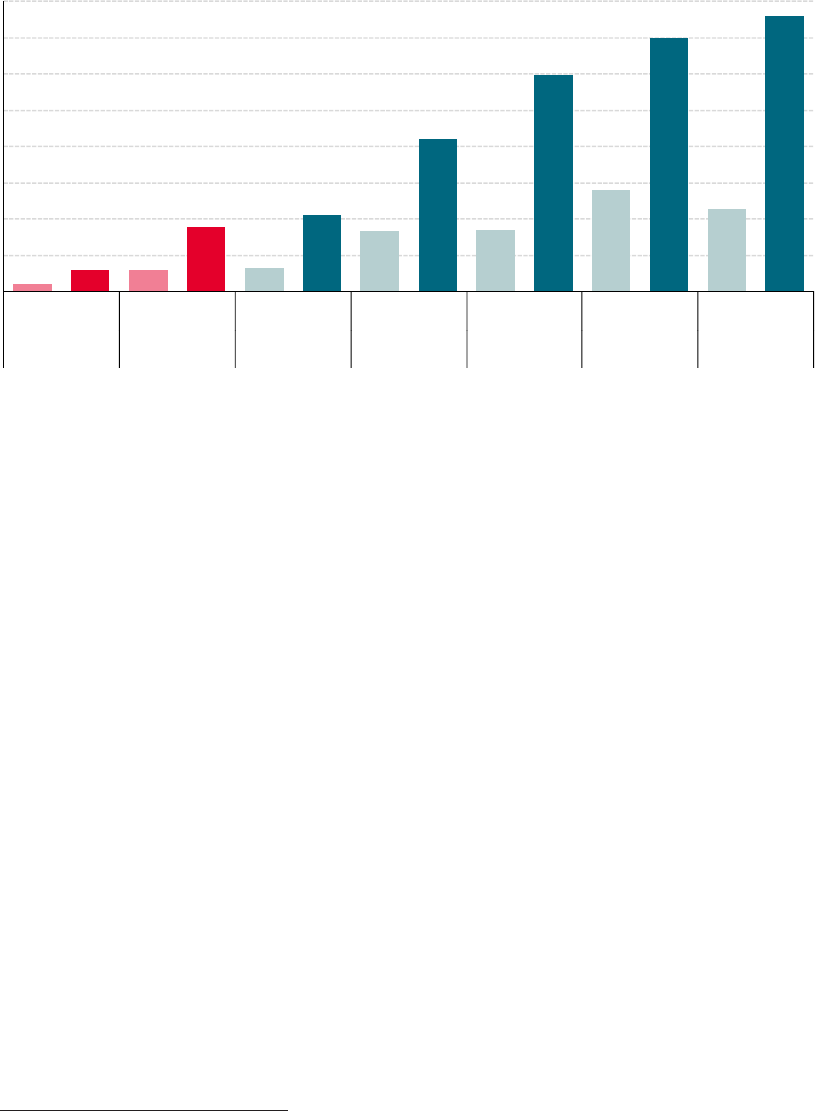

Figure 10 shows the fees for transferring funds from an e-wallet issued by a nonbank DSP in

selected countries.

22

This is the cost that a user must bear to transfer funds from an e-wallet

to an account outside the e-wallet’s platform. For Indonesia, the transfer always means a

transfer to a bank account. The figure shows that the fee for transferring funds in Indonesia

is comparatively high.

22

For most countries, we have data from one provider, except for Japan, the Philippines, and Thailand, from

which we have two. For Indonesia, the data are from the major nonbank DSPs. Because the cost is nominal,

we use the cost per 1,000 transactions, converted to US dollars and shown as percentage of daily GNI.

19

Figure 10. External transfer fees for e-wallet transfers, as percentage of daily

GNI per capita, Indonesia and selected comparator countries, 2020

Source: Compiled by authors from providers’ websites (see Appendix 2).

Note: For the first four countries in the figure, the box represents the 25th through 75th percentiles, and the large

dots represent the outliers. Only countries with available data are shown in the figure.

Figure 11 shows the fees for withdrawing money from a nonbank DSP across countries.

The bar for Indonesia represents the fact that in Indonesia nonbank DSPs are not allowed

to perform cash-out services. Along with the previous graph, this suggests that the binding

constraints on the expansion of e-wallet digital payment services might be on the supply side

of the decision tree.

20

Figure 11. External withdrawal fee from e-wallet, as percentage of daily

GNI per capita, Indonesia and selected comparator countries, 2020

Source: Compiled by authors from providers’ websites (see Appendix 2).

Note: In Indonesia, e-money issued by nonbank DSPs cannot be cashed out. Thus, we calculated two prices

for Indonesia. For people with bank accounts, the cost of withdrawing cash from their e-wallet consists of the

cost for transferring to their bank account plus the cost of withdrawing cash from that bank account. For those

without bank accounts, no cashing out is allowed, which is represented by the dark vertical bar in the figure. For

the first four countries in the figure, the box represents the 25th through 75th percentiles, and the large dots

represent the outliers.

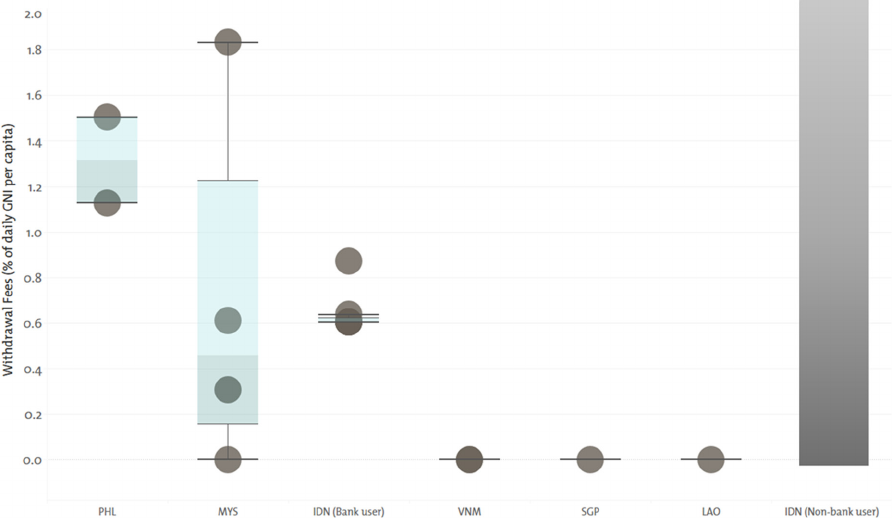

The fees related to the use of ATMs and e-wallets thus far point to binding constraints

on the supply side, which potentially limit the use of e-money to provide payment as well

as store-of-value services. The next set of figures shows the fees that are more relevant to

traditional store-of-value services provided by savings products.

Figure 12 shows the average fee for opening a bank account, and Figure 13 shows the average

fee for maintaining a regular savings account. Again, note that there are other, nonmonetary

costs associated with opening an account, such as access to the financial institution and

fulfilling application requirements related to KYC issues, that are not included in this analysis.

Fees charged in Indonesia are higher than in most of the other countries shown in Figures 12

and 13, again signaling that the binding constraints are on the supply side.

21

Figure 12. Average fees to open a regular savings account, as percentage of GNI

per capita, Indonesia and selected comparator countries, 2020

20.1%

19.3%

2.7%

0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0%

0%

Brunei

Lao PDR

Indonesia

China

India

Japan

Cambodia

Korea

Myanmar

Malaysia

New Zealan

d

Philippines

Thailand

Vietnam

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

Source: Compiled by authors from providers’ websites (see Appendix 2).

Figure 13. Average annual administrative fee to keep a bank account, as percentage

of daily GNI per capita, Indonesia and selected comparator countries, 2020

72.5%

57.8%

49.6%

37.8%

21.4%

14.5%

1.6%

0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0%0.0% 0.0% 0.0%

0%

20

%

40

%

60

%

80%

Brunei

Lao PDR

Indonesia

China

India

Japan

Cambodia

Korea

Myanmar

Malaysia

New Zealan

d

Australia

Singapore

Thailand

Vietnam

Source: Compiled by authors from providers’ websites (see Appendix 2).

To sum up, the fees for using regular savings accounts and e-wallets point to binding

constraints on the supply side that prevent providers from oering these services aordably.

We use these findings to guide our decision tree analysis in the following sections.

22

5. Supply-side constraints on payment

and store-of-value services

We will start our analysis by going through each node of the tree, keeping in mind the

observed (relatively high) fees discussed above. In keeping with the decision tree presented

in Section 3, we will first focus on whether some of the aspects of the market structure

of banks and other DSPs impose a binding constraint on the supply side. We then discuss

whether digital infrastructure is a binding constraint and evaluate whether there are problems

with investors’ appropriability of returns. Each of these nodes has dierent subsections that

address additional relevant factors.

5.1. Market structure of banks and nonbank digital

service providers

The high fees charged for the use of a financial service and the limited availability of

the product to a large segment of the population may be driven by a problematic market

structure in which imperfect competition and/or regulation drives prices up. We consider

two key factors characterizing the market structure dynamics. First, the regulatory

environment determines whether the existing regulations treat all providers oering the same

services the same way or give rise to an unlevel playing field between banks and other DSPs.

Second, the degree of competition between the providers may also impact the provision of

digital financial services; limited competition occurs when the number of providers is small.

The resulting limited competition can, in turn, cause a lack of interoperability between digital

networks that harms customers. These two factors appear as second-tier nodes under market

structure in the decision tree, and we assess each node using the price analysis and the other

methodology principles to determine whether each constitutes a binding constraint.

5.1.1. Unlevel playing field created by regulations

As discussed in Section 2, the current regulatory environment governing digital financial

services in the country reflects the combination of a set of new regulations designed

to specifically address the relatively new industry and the legacy of existing regulations

governing the traditional banking and financial industries. In this section we identify three

key issues stemming from the current regulations that create an unlevel playing field and,

in turn, are likely to aect fees, both directly and indirectly, and limit the supply of services.

The first issue is the restriction on cash-out services (cash withdrawals) that is imposed on

some, but not all, e-money providers. The second issue is the dierent restrictions on and

policies governing how dierent providers can recruit their agents. The third one is the

dierent regulations on how providers can conduct their KYC processes of verifying their

customers’ identities. Each of these may limit providers’ ability to increase the services they

oer existing customers as well as to expand their markets on the extensive margins, thereby

restricting the scope for financial inclusion. Next, we discuss how these key issues may create

an unlevel playing field and whether the unlevel playing field creates a binding constraint for

the expansion of digital financial services.

23

Restriction on cashing out and other services. BI regulations prevent nonbank digital

financial services providers’ agents from oering cash-out services. In order to be able to

provide cash-out services, e-money issuers must apply for a completely separate license

as money remitters, whereas branchless banking agents, which also provide services for

e-money transactions, are exempted from this requirement.

23

In addition, nonbank providers

wishing to provide person-to-person (P2P) transfers through their network of agents must

have each agent individually apply for a money remittance license, which is a burdensome

task. In fact, the requirement for a separate license may be one of the barriers preventing

MNOs from getting a foothold in the e-money market in Indonesia.

24

These regulations

prevent nonbank DSPs from oering full services, which limits their benefits to potential

customers and potentially curtails the demand for the products.

25

Users of a bank-issued e-wallet can withdraw cash from the bank’s agents as well as from the

bank’s ATMs. For most nonbank e-wallet users, the only way to withdraw cash from their

account is to send the money to a bank account and then withdraw money from that account

using the bank’s ATM. This regulation means that users without bank accounts have no easy

way to take cash out of their e-wallet. This obviously has some implications on the uptake

of the product itself, as customers may perceive fewer benefits due to the service limitations.

We analyze this last issue on the demand side in Section 6.1.

Further, the extra step for withdrawing money entails other costs, beyond the direct cost of

the withdrawal fee. The necessity of taking these additional steps could prove to be wasteful

in both time and money for users, especially given that the process has to be done repeatedly.

In conventional (bank) settings, the diculty of cashing out from a bank could be the

product of a lack of ATMs in a particular area. However, an increased penetration of ATMs

would not solve the problems created by the restriction on cash-out services from e-wallets.

Research has in fact suggested that robust cash-out (and cash-in) services may be necessary

for the growth of noncash payment products such as e-money (Hernandez 2019). Where

cash is still the dominant method of payment, such as in Indonesia, e-money users need to

be able to withdraw cash easily to perform transactions that cannot be done digitally.

26

23

Branchless banking agents are managed by the local branch of the bank, which is allowed to perform all kinds

of transactions.

24

If an MNO has a remittance license, to be able to take advantage of its network of airtime suppliers, each

supplier must apply for an individual remittance license (CGAP 2010). As discussed in Section 2, other barriers to

entry for MNOs include the requirement to include funds transfer as a business activity in the corporate articles,

which proves to be prohibitive for some publicly listed MNOs.

25

One argument put forward to justify the regulation was consumer security. Unlike money in savings accounts,

the funds stored in e-money are not protected by any kind of deposit insurance. Partly because of that, the

functionality of e-money in Indonesia is geared toward payment services, in which the amounts involved are

relatively small, rather than store-of-value services. Ability to cash out may cause users to keep a higher balance

in their e-wallet, turning it, functionally, into a savings product. Granted, this argument is at odds with the

government’s push to digitize social assistance so that the poor population can start saving by not withdrawing the

full amount of the social assistance payment, in eect treating the social assistance e-wallet as a savings account.

More important, this reasoning contradicts the goal of using e-money to increase financial inclusion.

26

E-money users also need to be able to top up their e-wallets conveniently at points of service. This means easy

access to agents that can provide cash-in services is also important, as discussed next.

24

Recently, GoPay has formed a strategic alliance with one of the largest private banks, Bank

Central Asia (BCA), that allows GoPay users to withdraw funds from the partner bank’s

ATM without administrative fees and without a requirement that users have an account at

BCA. BCA charges a withdrawal fee of 5,000 Indonesian rupiahs (IDR; about US$0.35).

This fee, however, is lower than the withdrawal fee for other banks’ debit cards when using

BCA’s ATM, which is around IDR 6,500. Previously, users of a non–BCA e-wallet (or bank)

service would have to go through the extra step of moving their e-wallet balance to their

bank account first, and then withdrawing the money afterwards.

27

Applying principle 3 of the decision tree methodology to identify a binding constraint, the

discussion above shows a clear example of actors finding a way to circumvent the constraint.

There are several reasons why BCA may benefit from the partnership with GoPay. First, it

may be able to tap into the huge network of GoPay users, leading to a significant increase

in the usage of the BCA ATM network.

28

Second, since BCA is allowed to charge a fee for

these withdrawals, the partnership can be lucrative for both parties. This is, however, an

exception to a system in which generally, individuals find severe diculties in withdrawing

money from e-money services, negatively impacting their customer experience.

Finally, on top of the shadow costs, direct costs are also typically incurred by e-wallet users

transferring funds to banks. Generally, transferring to a bank incurs a small transfer fee.

While this fee is similar to an interbank transfer fee in a conventional setting, the relative

availability of ATMs in recent years has made bank accounts more attractive than e-money

options, at least in terms of cash-out services.

The combination of the above-mentioned shadow and direct costs for cashing out may well

explain the reluctance of Indonesian users to store high values of funds in their e-wallet

accounts, and hence the low prevalence of e-wallet use for nonpayment purposes in the

Indonesian market.

Note that cash-out restrictions do not apply to BSAs. BSA customers can withdraw cash

at branchless banking agents and, if the BSA account comes with an ATM card, they can

withdraw cash from an ATM. Thus, this constraint is potentially binding for nonbank

e-money services, but not for BSAs.

Restrictions on and policies governing agents’ recruitment. At least two opposing

forces are at work to create an unlevel playing field in agent recruitment. On the one hand,

under the branchless banking model, banks are allowed to recruit agents to provide digital

financial services with dierent requirements from those imposed on nonbank DSPs. In

particular, BI Regulation No. 20/6/PBI/2018 provides that while digital finance agents can

27